Introduction

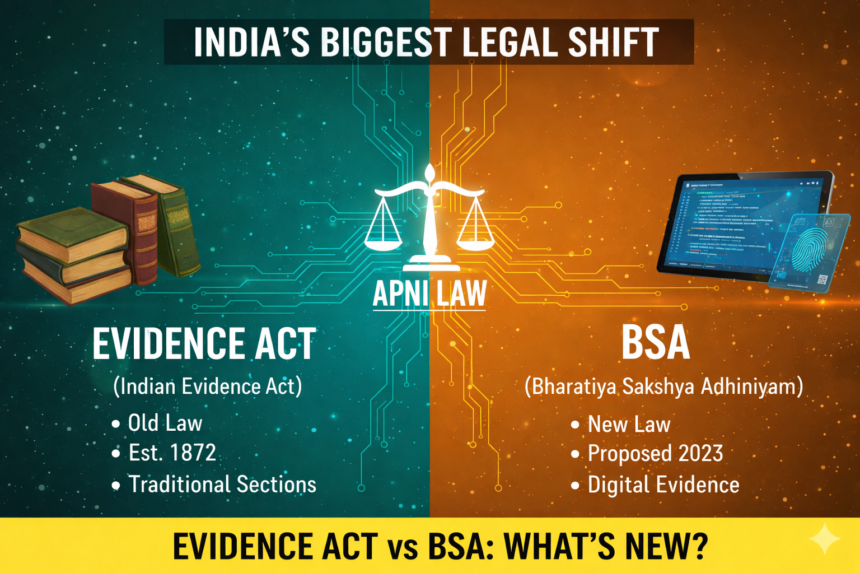

Electronic evidence has become central to modern litigation. Emails, WhatsApp chats, CCTV footage, call data records, and server logs are now routinely produced before courts. In India, the law governing such evidence has recently undergone a major shift. Section 65B of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 earlier controlled this field. From 1 July 2024, it stands replaced by Section 63 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam, 2023. While the new law modernises the language and structure, it largely preserves the core principles laid down by judicial interpretation over the last decade.

What Was the Purpose of Section 65B of the Indian Evidence Act?

Section 65B was introduced to address a unique problem. Electronic records cannot always be produced in their original form. Digital data exists in intangible formats and is easily alterable. Section 65B created a special rule to treat computer outputs as documents. It allowed printouts, CDs, pen drives, or other electronic copies to be admitted as evidence without producing the original device. This special treatment, however, came with strict safeguards to ensure authenticity and reliability.

How Does Section 63 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam Replace Section 65B?

Section 63 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam, 2023 is the successor to Section 65B. It governs electronic and digital records under the new evidence regime. The legislature has consciously retained the structure of Section 65B while expanding its scope. The intention is continuity rather than disruption. Courts familiar with Section 65B jurisprudence will find Section 63 largely familiar, though better aligned with present-day technology.

What Conditions Must Be Satisfied for Electronic Evidence to Be Admissible?

Both Section 65B and Section 63 impose mandatory technical conditions. These conditions focus on the reliability of the system from which the electronic record is produced. The computer or device must have been used regularly. The information must have been fed into the system in the ordinary course of activities. The device must have been functioning properly at the relevant time. If there was any malfunction, it should not have affected the accuracy of the record. Finally, the output must faithfully reproduce the original input. These conditions are treated as foundational requirements, not procedural formalities.

Why Is the Certificate Requirement So Important?

The certificate requirement is the heart of electronic evidence law in India. Under Section 65B(4) of the old Act and Section 63(4) of the new Act, a certificate is mandatory. This certificate authenticates the electronic record. It confirms the manner of its production. It identifies the device used. It certifies compliance with statutory conditions. The Supreme Court has repeatedly held that without this certificate, electronic evidence is inadmissible. The landmark judgments in Anvar P.V. v. P.K. Basheer and Arjun Panditrao Khotkar v. Kailash Kushanrao Gorantyal settled this position conclusively.

Who Can Issue the Certificate Under the New Law?

Under Section 65B, the certificate had to be signed by a person occupying a responsible official position in relation to the operation of the device or management of relevant activities. Section 63 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam widens this framework. It allows the certificate to be issued by such a person and an expert. This change recognises the growing complexity of digital systems. Expert involvement enhances credibility, especially in cases involving forensic extraction, cloud servers, or complex networks.

Does the New Law Expand the Meaning of Electronic Records?

Yes, the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam adopts broader and more contemporary terminology. While Section 65B primarily referred to “computer output,” Section 63 uses the expression “electronic and digital records.” This aligns the law with evolving forms of data storage, including mobile devices, virtual servers, and online platforms. The expansion ensures that the law remains technologically neutral and future-ready.

How Does the New Act Treat Electronic Evidence as Primary Evidence?

Under the Indian Evidence Act, electronic records were linked indirectly to the provisions on primary and secondary evidence. The Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam clarifies this relationship. Section 62 of the new Act explicitly recognises electronic records within the framework of primary evidence. Section 63 then provides the mechanism for admitting electronic copies subject to certification. This structural clarity reduces interpretational confusion and streamlines courtroom practice.

What Is the Role of Expert Opinion Under the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam?

The new law strengthens the evidentiary value of expert analysis. Section 39(2) of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam directly recognises the relevance of the opinion of an examiner of electronic evidence. Earlier, courts relied on Section 79A of the Information Technology Act indirectly. The express inclusion under the evidence law itself improves coherence and reinforces the reliability of digital proof.

Which Law Applies to Pending and Future Cases?

The Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam applies to proceedings instituted on or after 1 July 2024. Cases initiated before this date continue to be governed by the Indian Evidence Act. However, judicial reasoning developed under Section 65B remains highly persuasive for interpreting Section 63. Practitioners must therefore understand both regimes to effectively handle transitional litigation.

Conclusion

Section 63 does not dilute the strict standards laid down under Section 65B. Instead, it refines them. It simplifies language, expands scope, and acknowledges expert involvement. The emphasis on authenticity, integrity, and reliability remains unchanged. Courts are likely to continue rejecting uncertified electronic evidence. At the same time, genuine digital records supported by proper certification will face fewer procedural hurdles.