Introduction

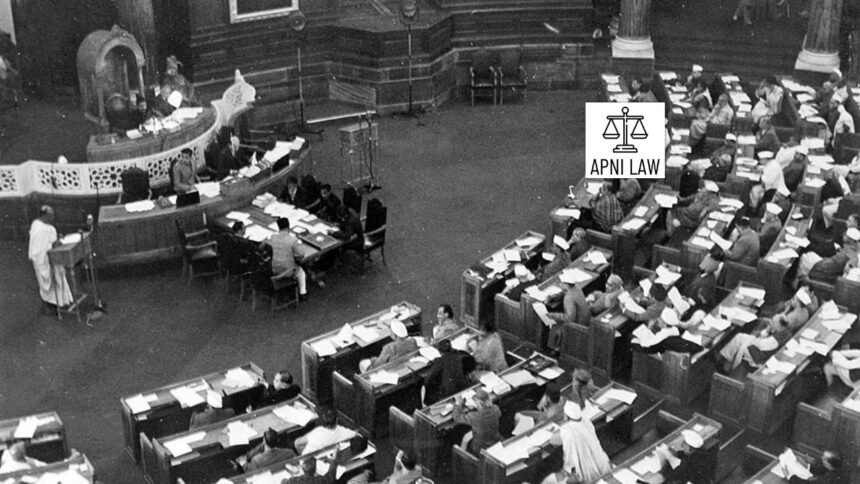

The Indian Constituent Assembly was not merely an instrument of legislation but also a forum for vociferous debates that determined the fate of the Republic. Between 1946 and 1949, its members debated vehemently about issues that perturbed the very substratum of the country. Federal issues, the position of language, and the safeguarding of minority rights were at the core of these debates. These debates alluded to the diversity of India, the challenges of Partition, and the competing aspirations of communities.

The Assembly’s capacity for conciliation without compromise on democratic ideals was impressive. Analyzing these debates provides us with insights as to why the Indian Constitution took the form it did and how the Constitution continues to balance unity and diversity.

Federalism: Centre versus States

The most contentious debate within the Constituent Assembly was over how to divide powers between the Union and states. India had emerged out of colonialism divided by princely states, provincial borders, and the wounds of Partition. Many leaders believed that a firm central government was necessary to preserve unity and stability.

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, popularly referred to as the “Iron Man of India,” strongly advocated granting the Centre overriding powers. He felt that in the absence of strength at the Centre, India would disintegrate, particularly after the agonizing experience of Partition. Most agreed with Patel, and the Constitution ultimately conferred high powers on the Union in regard to subjects such as defense, foreign affairs, and matters of emergency.

Still, there were voices of leaders like K.C. Reddy and others in favor of more autonomy to the states, as over-centralization might dilute federalism. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar defended the provisions of the Drafting Committee by pointing out that India was “federal in structure but unitary in spirit.” The balance saw that states enjoyed independence in matters at the local level but the Centre was strong enough to safeguard national unity.

This accommodation forged India’s distinctive model of federalism. As opposed to the United States’ or Canadian rigid federal systems, India’s system tilted towards a powerful Centre but yet allowed for regional diversity.

The Language Question: Hindi vs. Diversity

Quite possibly the most passionate arguments in the Constituent Assembly involved language. India’s remarkable linguistic heterogeneity made deciding on a national language no easy matter. The Hindi-speaking representatives, under the leadership of figures such as R.V. Dhulekar, were adamant that Hindi in the Devanagari script should be made the national language. They claimed that Hindi was the language spoken by the greatest number of people and could unite the country.

This stance, however, was strongly opposed by members belonging to non-Hindi speaking areas, particularly the South. T.T. Krishnamachari, representing Madras, cautioned that imposing Hindi might alienate vast sections of the population and even jeopardize national unity. Leaders of Bengal and other provinces also voiced similar apprehensions.

Later, a compromise was made. Hindi in the Devanagari script was made the official language, but English remained an associate official language for 15 years. This deal, the “Munshi-Ayyangar formula,” provided states with a latitude to employ their regional languages for official purposes.

This controversy demonstrated the sensitivity of the Assembly to India’s pluralism. Although it acknowledged the unifying function of Hindi, it was also mindful of the linguistic rights of other states that were not Hindi-speaking. This compromise still influences India’s language policy today, with various languages existing side by side under the constitutional order.

Minority Rights: Balancing Protection and Integration

Another key area of contention was the safeguard of minority rights. Partition had instilled profound fears among religious and cultural minorities, especially Muslims and Christians, who were apprehensive of being marginalized in a Hindu-dominated country. Members such as H.C. Mookherjee and Frank Anthony vehemently pushed for protection to guarantee minorities to maintain their culture, identity, and schools.

Conversely, others such as Sardar Patel maintained that the provision of excessive communal safeguards would promote separatism and dilute the national unity sense. Patel was of the opinion that post-Partition, India could not pursue policies dividing people on a religious basis.

The Assembly finally came to a balance. The Constitution secured minorities’ cultural and educational rights in Articles 29 and 30 of the Constitution, enabling them to maintain their language, script, and culture. Simultaneously, minority separate electorates, which had previously been a cause of sharp division, were rejected categorically. In their place, universal adult franchise was embraced, providing each citizen with an equal vote irrespective of religion or community.

This choice expressed a deliberate attempt to bring minorities into the folds of the democratic system without compromising their cultural identities. It established the basis for India’s secular democracy, with all communities sharing equal rights under a single Constitution.

The Spirit of Debate and Compromise

What rendered these debates historic was not only the pungency of arguments but also the atmosphere of compromise that dominated. Members frequently disagreed on federal powers, language, and minority protection but realized the importance of agreement. A leader such as Rajendra Prasad, who had the honor of chairing the Assembly, made sure that dissident opinions were heard and honored.

The debates demonstrated that the Constitution had not been imposed by a majority but was the result of dialogue, persuasion, and compromise. Each decision was reached with thoughtful regard for India’s diversity and history. The outcome was a Constitution that was inclusive and yet malleable and could keep a nation as diverse as India together.

FAQ

What was the central debate on federalism in the Constituent Assembly?

The major issue of contention was whether India needed a powerful Centre or give greater autonomy to states. The Assembly promoted a strong Centre with the continuation of state powers for local administration.

How did the Assembly settle the language issue?

It made Hindi in Devanagari script the official language but provided English with the status of an associate official language for 15 years, with freedom for states to adopt regional languages.

What protections were afforded to minorities in the Constitution?

Minorities received cultural and educational rights but not separate electorates to ensure national unity.

Conclusion

The controversies within the Constituent Assembly indicate the intensity of thinking and the gravity with which India’s leaders treated nation-building. Federalism, language, and minority rights were not matters of abstractions but issues that concerned millions of people. The success of the Assembly was to seek middle courses between centralized power and state autonomy, between Hindi and linguistic pluralism, and between minority protection and national integration.

These concessions gave birth to a Constitution that has survived for over seven decades. The atmosphere of discussion and consensus that presided over the Assembly is an example for democratic leadership even now. The Indian Constitution remains true to the vision of its architects who boldly imagined unity in diversity through discussion, give-and-take, and collective sagacity.

For any specific query call at +91 – 8569843472