Introduction

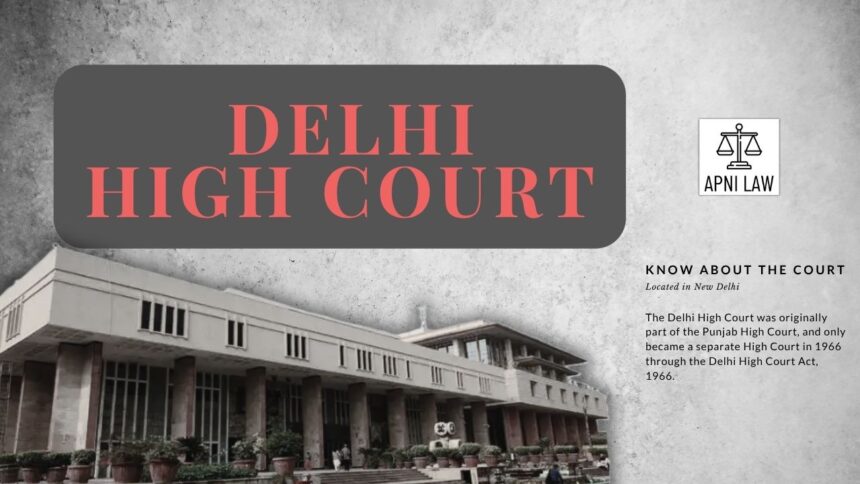

The Delhi High Court has clarified that a woman’s entitlement under Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (PWDV Act) to a “shared household” does not grant her a licence to live indefinitely in her in-laws’ property. The court said this right is protective in nature, not a right of ownership. The decision re-frames how courts must handle residence claims where senior citizens own the property. This ruling balances the woman’s need for protection with the elderly owners’ right to peaceful possession.

Facts of the Case

A woman had appealed against a lower court’s order that directed her to vacate her in-laws’ home. She had argued that the house counted as a “shared household” under Section 17 of the PWDV Act and so she could continue living there. The in-laws, who were senior citizens, claimed that the property was self-acquired and part of their personal assets. They argued that continued co-residence with the daughter-in-law had become harmful to their peace, health, and dignity. The Single Judge had ordered that she vacate the premises within two months, but also provided interim relief: alternate accommodation and monthly maintenance for her and the children, funded by the husband or in-laws. The woman challenged this order.

What the Court Says

A division bench of the Delhi High Court, presided over by Anil Kshetarpal and Harish Vaidyanathan Shankar, dismissed her appeal. The court held that her statutory right under the PWDV Act is a right of protection. It is not a right to ownership or a permanent licence to occupy property belonging to others.

The bench relied on previous rulings, including Manju Arora v. Neelam Arora & Anr., where courts held that a daughter-in-law cannot insist on indefinite stay in the in-laws’ home when the arrangement has become harmful to them.

The court stressed that the right of residence must be balanced with the senior citizens’ right to peaceful and dignified living in their own home. If continuing co-residence aggravates the elderly’s medical or mental condition, their right to enjoy their property outweighs the daughter-in-law’s claim.

In this case, the court found that continued residence caused “manifest hardship” to the in-laws. It held that the Single Judge’s interim arrangement, offering alternative accommodation to the woman and maintenance for her children, was fair and proportionate. The court observed that granting protection under the PWDV Act does not require seniors to endure “a corrosive domestic environment.”

The court also clarified that this outcome did not leave the woman destitute or homeless. The alternate accommodation offered was of comparable standard and was funded by the in-laws.

Thus, the court reaffirmed that the residence right under Section 17 is neither absolute nor permanent. It does not convert into a proprietary or indefeasible right.

Implications

This judgment sends a strong message: protective laws cannot be used as a shield for indefinite occupation of self-acquired family property. Courts must balance the right of a woman to protection with the property rights and dignity of senior citizens. Legal practitioners must note that residence under the PWDV Act does not create ownership or permanent tenancy. Where co-residence becomes harmful, courts can and will order eviction, provided alternate accommodation and maintenance are secured.

The ruling also clarifies that relief under the PWDV Act aims to prevent homelessness or destitution, not to grant perpetual residence. It preserves the core purpose of the Act while preventing abuse of its provisions.

The website of the Faculty of Law and Political Science at the University of M’Sila serves as a comprehensive academic portal for students, faculty members, and researchers. It provides access to exam schedules, results, study documents, and official announcements, along with detailed information about undergraduate and postgraduate programs in law and political science. The platform also highlights the faculty’s scientific journals and research activities, offering a valuable space for academic publication and knowledge exchange. Overall, the website reflects the faculty’s commitment to transparency, quality education, and supporting students throughout their academic journey.