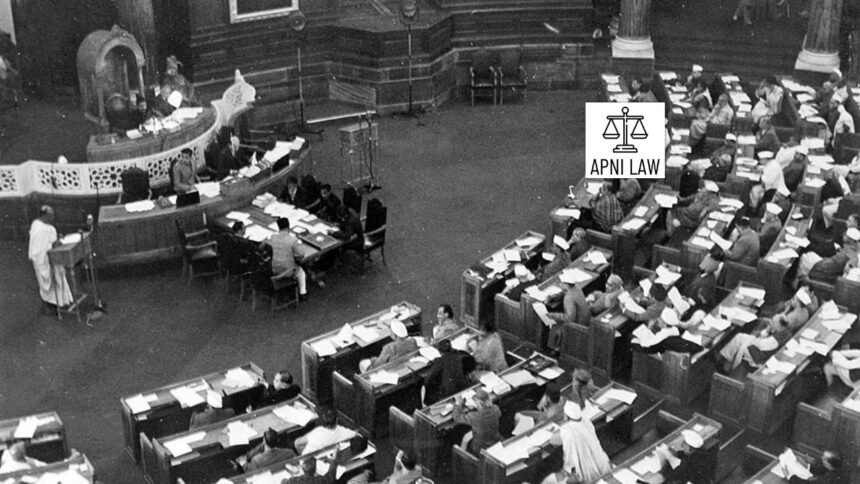

Introduction

The idea of Fundamental Duties in the Indian Constitution took shape during a critical period in Indian politics. In 1976, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi set up the Swaran Singh Committee to recommend ways to strengthen constitutional obligations of citizens. The committee, chaired by Dr. Swaran Singh, submitted a detailed report that laid the foundation for introducing duties into the Constitution. These recommendations eventually became part of the 42nd Constitutional Amendment Act, 1976, which inserted Article 51A in Part IV-A. The inclusion of duties was seen as a balancing element to the Fundamental Rights guaranteed to citizens. Although not all recommendations were accepted, the committee’s work left a lasting imprint on Indian constitutional law.

What Are The Original Recommendations of the Committee

The committee suggested eight core duties that every citizen should follow. It emphasized that citizens must respect and abide by the Constitution and the laws made under it. It stressed the importance of upholding the sovereignty, unity, and integrity of India, especially in the context of national security and stability.

Another important recommendation was to respect democratic institutions. The committee believed that citizens should not act in ways that would impair the dignity or authority of institutions that safeguard democracy. It also urged that defending the country should be considered a duty for every Indian, and rendering national service, including military service when required, should be part of this obligation.

The committee placed strong emphasis on national integration and suggested that citizens must abjure communalism in all forms. At a time when communal tensions often disturbed social harmony, this recommendation carried special significance. The committee also linked citizen duties with the Directive Principles of State Policy. It said that citizens should assist the State in implementing these principles and work to promote social and economic justice.

The committee further recommended that citizens must abjure violence, protect public property, and refrain from damaging or destroying it. This suggestion reflected growing concerns about violent protests and destruction of government assets during political movements in the 1970s. Lastly, the committee proposed that every citizen should pay taxes honestly according to the law. It viewed tax payment as a civic duty essential for nation-building and economic stability.

Additional Suggestions

The Swaran Singh Committee went beyond listing duties and also recommended certain mechanisms for enforcement. It advised that Parliament should prescribe penalties for non-compliance with Fundamental Duties. According to the committee, mere declaration of duties would not be enough unless backed by legal consequences.

It further proposed that any law imposing penalties for violation of these duties should not be challenged in courts on the ground of infringement of Fundamental Rights. This recommendation attempted to give duties a stronger constitutional status by insulating them from judicial review. Essentially, the committee wanted duties to have enforceability and not remain only as moral obligations.

Implementation through 42nd Amendment

The Congress government led by Indira Gandhi accepted the idea of including duties in the Constitution but did not adopt all recommendations. Most notably, the duty to pay taxes and the provision for penalties were excluded. Despite this, the 42nd Constitutional Amendment Act, 1976 introduced ten Fundamental Duties in Article 51A. These duties went beyond the eight suggested by the committee and expanded the scope of citizen obligations.

The ten duties required citizens to respect the Constitution, the National Flag, and the National Anthem. They included the duty to cherish noble ideals of the freedom struggle, uphold sovereignty and unity, defend the country, promote harmony and the spirit of common brotherhood, preserve the rich heritage of the nation, protect the environment, develop scientific temper and humanism, safeguard public property, and strive for excellence.

In 2002, the 86th Constitutional Amendment Act added an eleventh duty. It made it the duty of every parent or guardian to provide opportunities for education to their children between the ages of six and fourteen. This amendment linked duties with the newly added Fundamental Right to Education under Article 21A.

Legacy of the Committee’s Work

The Fundamental Duties introduced in 1976 reflect the influence of the Swaran Singh Committee. However, unlike Fundamental Rights, these duties are non-justiciable. This means that citizens cannot be legally compelled by courts to perform them. They remain moral obligations rather than legally enforceable commands.

Despite this limitation, the judiciary has often referred to Fundamental Duties while interpreting constitutional provisions. In cases involving environmental protection, heritage conservation, or public property, courts have invoked Article 51A to remind citizens of their obligations. For example, the Supreme Court in AIIMS Students Union v. AIIMS (2002) highlighted that Fundamental Duties are equally important as Fundamental Rights in ensuring constitutional balance.

The committee’s suggestion on penalties was not accepted. Critics argued that such enforcement could give excessive powers to the government and curtail individual freedoms. Yet, some existing laws indirectly reflect these duties. For instance, laws that punish destruction of public property or laws mandating respect for national symbols align with the spirit of duties recommended by the committee.

Criticism of the Recommendations

Scholars and jurists have pointed out several weaknesses in the Fundamental Duties introduced on the basis of Swaran Singh Committee’s report. First, the exclusion of the duty to pay taxes has been criticized. Many believe that tax compliance is one of the most practical forms of civic responsibility, and excluding it reduced the seriousness of the scheme.

Second, some critics argue that duties such as developing scientific temper or promoting harmony are vague and difficult to measure in practical terms. These duties appear more moralistic than legal in character. Others highlight that crucial duties like casting votes or family planning were never included, despite being important for a democratic and welfare-oriented society.

The timing of the recommendations also drew suspicion. The committee worked during the Emergency period (1975–77) when civil liberties were under strain. Many critics argue that the government pushed for Fundamental Duties to shift the focus from rights to obligations, thereby controlling dissent. This political backdrop has influenced how people view the Swaran Singh Committee and its recommendations.

Impact on Constitutional Development

The Swaran Singh Committee created an important precedent by formally introducing the idea of Fundamental Duties. Today, India has eleven duties, and they continue to guide civic behavior. While they remain non-justiciable, their moral and educational value is significant. Schools and institutions often teach them to instill civic sense among students.

The judiciary has also kept duties alive in constitutional discourse. For example, in MC Mehta v. Union of India (1988), the Supreme Court linked environmental protection to citizens’ duties under Article 51A(g). Similarly, in cases concerning heritage sites, courts have reminded citizens of their duty to preserve the nation’s rich cultural heritage.

The duties also serve as a reminder that rights and obligations go hand in hand. They complement the Directive Principles of State Policy, which aim at achieving social and economic justice. Together, rights, duties, and directive principles form the ethical foundation of the Constitution.

For any specific query call at +91 – 8569843472

Conclusion

The Swaran Singh Committee’s recommendations on Fundamental Duties reshaped the Indian constitutional framework in 1976. Although not all suggestions were accepted, the introduction of ten duties and the later addition of an eleventh duty reflected the spirit of the committee’s work. These duties, though non-justiciable, remain an essential moral code for citizens. They encourage respect for the Constitution, preservation of national unity, protection of heritage and environment, and active participation in nation-building.

Criticism about vagueness, exclusion of voting or tax payment, and political motives during the Emergency still surrounds the legacy of the committee. Yet, the fact remains that Fundamental Duties continue to influence civic life, judicial reasoning, and constitutional education. The Swaran Singh Committee succeeded in embedding a sense of responsibility into the constitutional scheme, making it clear that rights cannot stand in isolation without duties.