Introduction

Section 24 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 and Section 22 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam, 2023 deal with involuntary confessions. Both provisions protect accused persons from being convicted on the basis of confessions obtained through unfair means. The law rejects confessions that arise from inducement, threat, promise, or coercion. The core idea remains voluntariness. A confession must be free, voluntary, and made without improper influence. The Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam continues this principle without changing its substance.

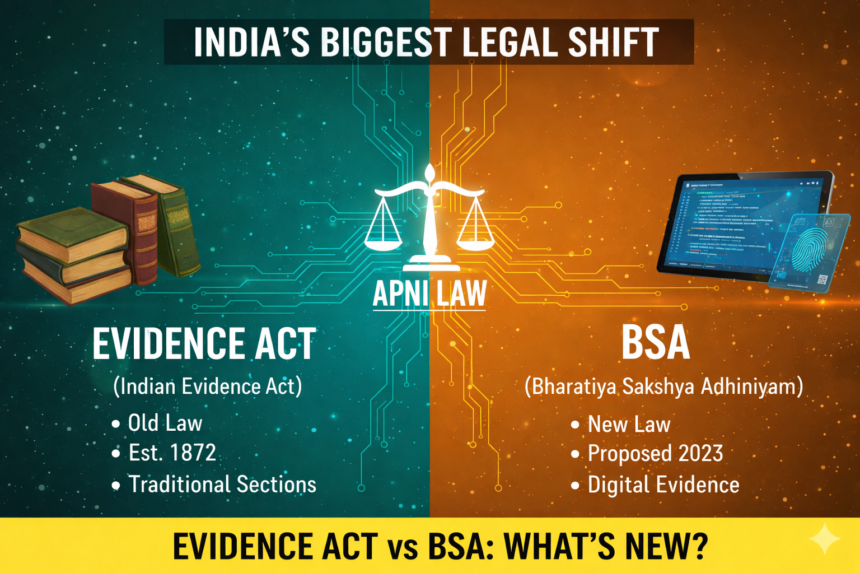

How does Section 22 BSA differ from Section 24 of the Evidence Act?

Section 22 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam modernises the language of Section 24 of the Evidence Act. It also expressly adds the word “coercion.” This addition does not change the law in practice. Courts already treated coercive conduct as invalidating a confession under Section 24. The new wording merely clarifies the position. The structure and legal effect remain the same. Section 22 functions as a direct successor to Section 24.

What is the statutory rule on confessions under both laws?

Both provisions state that a confession becomes irrelevant in a criminal proceeding if the court finds that it was caused by inducement, threat, promise, or coercion. The influence must relate to the charge. It must come from a person in authority. It must be strong enough to make the accused reasonably believe that confessing would bring some benefit or avoid some harm of a temporal nature. If these conditions exist, the court must exclude the confession from evidence.

Who can make a confession under these provisions?

The confession must be made by an accused person. Courts interpret this term broadly. A person need not be formally charged at the time of making the confession. If the prosecution relies on the statement against that person, the law treats him as an accused. This interpretation continues unchanged under the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam.

What does “caused by inducement, threat, promise or coercion” mean?

The court looks for a causal connection. It must appear that the improper influence led to the confession. The influence may take many forms. It may involve assurance of leniency. It may involve fear of arrest, torture, or prolonged detention. Under the BSA, coercion is now expressly mentioned. However, the principle remains the same. Any pressure that destroys free choice makes the confession involuntary and unreliable.

Who qualifies as a “person in authority”?

A person in authority is someone who has real or apparent control over the accused or the proceedings. Police officers clearly fall within this category. Magistrates and investigating officials also qualify. Even private persons may count if they appear capable of influencing the outcome of the case. This concept remains identical under both statutes. Courts assess authority based on facts, not formal titles.

What is meant by “reference to the charge”?

The inducement or threat must relate to the offence under inquiry. General moral persuasion does not attract the section. The influence must connect the confession with the criminal case. If the accused believes that confessing will affect the investigation, trial, or punishment, the requirement stands satisfied. Both Section 24 and Section 22 retain this requirement.

What is a “temporal advantage or evil” in confession law?

The law focuses on worldly benefits or harms. Temporal advantage includes lighter punishment, bail, release from custody, or favourable treatment. Temporal evil includes arrest, physical harm, harassment, or prolonged detention. Spiritual or moral inducements do not fall within this category. The Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam preserves this classic distinction.

How does the court test voluntariness of a confession?

The court applies a mixed objective and subjective test. It examines whether the circumstances could give reasonable grounds to the accused to believe in the promised benefit or threatened harm. The court does not require proof of actual influence. Appearance of causation is enough. This standard continues without modification under Section 22 BSA.

When does a confession become admissible despite earlier inducement?

Both provisions contain the same saving clause. If the confession is made after the impression of inducement, threat, promise, or coercion has been fully removed, the confession becomes relevant. The court must be satisfied that the accused regained free will. This safeguard exists in both the old and the new law.

Do secrecy, deception, or lack of warning invalidate a confession?

The law clearly answers this question. A confession does not become irrelevant merely because it was made under a promise of secrecy. Deception used to obtain a confession does not automatically invalidate it. Confessions made while drunk remain admissible if voluntary. Answers to improper questions do not alone vitiate a confession. Failure to warn the accused also does not make it inadmissible. These rules continue unchanged under Section 22 BSA.

Does old case law under Section 24 still apply?

Yes. Judicial interpretations of Section 24 of the Evidence Act remain fully relevant. The Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam does not alter the doctrine. Courts will rely on established precedents unless constitutional or statutory developments demand otherwise. The continuity of principle is clear and deliberate.

Conclusion

Section 22 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam restates Section 24 of the Evidence Act with clarity and modern drafting. The foundation remains voluntariness. The protection against involuntary confessions remains intact. The addition of the word “coercion” strengthens clarity, not substance. In practice and theory, the rule continues unchanged.