Introduction

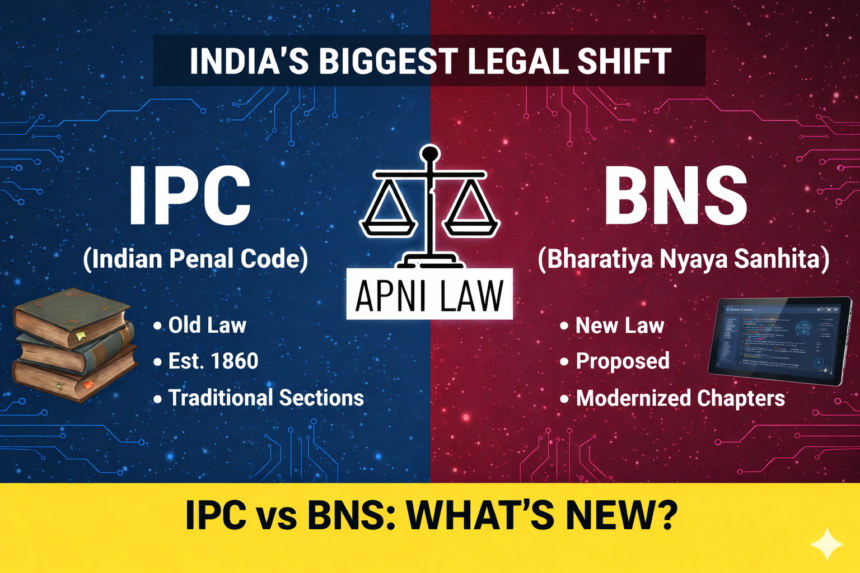

The offence of rape occupies a deeply sensitive and serious space in Indian criminal law. It involves not only physical violence but also grave violations of dignity, autonomy, and bodily integrity. For decades, Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860, defined rape and shaped the legal understanding of sexual offences in India. Judicial interpretation and legislative amendments, especially after the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 2013, significantly expanded its scope. With the introduction of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, Section 63 replaces Section 375 IPC. While the core principles remain intact, the new provision attempts to simplify language, remove colonial phrasing, and reflect constitutional values more clearly.

What did Section 375 IPC define as rape?

Section 375 IPC defined rape through six descriptions, focusing on acts involving penile penetration under specific circumstances. These circumstances included absence of consent, consent obtained by fear or misconception, consent given due to intoxication or unsoundness of mind, consent by a woman under eighteen years of age, and situations where the woman was unable to communicate consent.

After the 2013 amendment, the definition expanded significantly. It included penetration of any extent, oral acts, and insertion of objects, thereby recognising the varied forms of sexual violence. Consent was explicitly defined as an unequivocal voluntary agreement, shifting the focus from resistance to willingness. This amendment marked a turning point in rape jurisprudence by centring the woman’s autonomy.

How does Section 63 BNS redefine rape?

Section 63 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita substantially carries forward the definition provided under Section 375 IPC. The acts constituting rape and the circumstances negating consent remain largely unchanged. However, the drafting under the BNS adopts clearer and more direct language. It removes archaic expressions and restructures the provision to improve readability and accessibility.

The emphasis on consent remains central under Section 63 BNS. Consent continues to mean a clear and voluntary agreement, communicated through words or conduct. Silence or lack of physical resistance does not amount to consent. By retaining this understanding, the BNS ensures continuity with progressive judicial interpretations developed over the years.

Has the concept of consent changed under BNS?

The conceptual understanding of consent under Section 63 BNS remains consistent with the post-2013 IPC framework. Courts must still examine whether consent was free, informed, and voluntary. The law continues to protect women from situations where consent is obtained through coercion, deception, abuse of authority, or mental incapacity.

Judicial precedents such as State of Punjab v. Gurmit Singh and Pramod Suryabhan Pawar v. State of Maharashtra remain relevant in interpreting consent under the BNS. These decisions emphasise that consent obtained on false promises or under pressure lacks legal validity. The BNS does not dilute these protections but reinforces them through clearer statutory language.

What about marital rape under Section 63 BNS?

One of the most debated aspects of rape law is the marital rape exception. Like Section 375 IPC, Section 63 BNS retains the exception that sexual intercourse by a man with his own wife, provided she is not under eighteen years of age, does not amount to rape. This continuation has drawn criticism from scholars and activists who argue that it contradicts constitutional principles of equality and bodily autonomy.

Although the BNS does not remove this exception, ongoing constitutional challenges and evolving judicial discourse suggest that this area of law may witness future reform. For now, the legal position under both IPC and BNS remains the same.

Does Section 63 BNS improve victim-centric justice?

While Section 63 primarily defines the offence, it functions within a broader reformative framework introduced by the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita. The new criminal law ecosystem places greater emphasis on speedy investigation, victim compensation, and procedural safeguards. These changes indirectly strengthen the enforcement of rape laws by reducing secondary victimisation.

The simplified structure of Section 63 also helps survivors, investigators, and courts understand the law more clearly. This clarity reduces interpretative confusion and promotes consistent application.

What is the overall legal impact of the change?

The transition from Section 375 IPC to Section 63 BNS represents continuity rather than disruption. The substance of rape law remains progressive and survivor-centric. At the same time, the BNS modernises statutory language and aligns the provision with constitutional morality and contemporary legal thought.

Rather than reinventing the offence, the BNS consolidates decades of judicial development into a clearer and more accessible format. This approach ensures stability while improving legal clarity.

Conclusion

Section 63 BNS replaces Section 375 IPC without weakening the legal protection against rape. The definition of the offence, the centrality of consent, and the recognition of sexual autonomy remain firmly intact. The key change lies in improved legislative drafting and integration with a reform-oriented criminal justice system. While certain unresolved issues such as marital rape persist, the new provision reinforces India’s commitment to dignity, equality, and justice for survivors of sexual violence.