Introduction

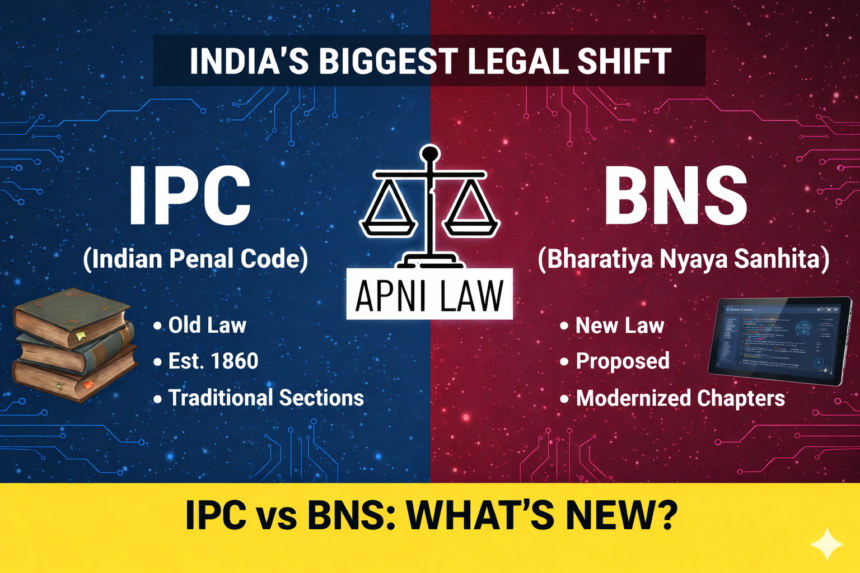

Section 321 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, traces its roots directly to Section 415 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. The legislature did not alter the soul of the offence. Cheating continues to rest on deception. The law still punishes dishonest or fraudulent inducement that leads a person to act against their interest. Both provisions focus on conduct that causes wrongful loss to one person and wrongful gain to another.

Under both laws, cheating occurs when a person intentionally deceives another. The deception must induce the victim to deliver property, allow the retention of property, or do or omit an act they would not have done otherwise. The result must be harm or the likelihood of harm. This harm may affect property, body, mind, or reputation. The BNS preserves this structure and ensures continuity with long-standing judicial interpretation.

Does the BNS Change the Core Ingredients of Cheating?

The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita does not change the essential ingredients of cheating. The core elements remain intact. The prosecution must still establish deception, inducement, and resulting harm. The emphasis on intention remains strong. The accused must have dishonest or fraudulent intent at the very time the inducement takes place.

Courts have repeatedly held that a promise made in good faith, even if later broken, does not amount to cheating. The BNS continues to uphold this distinction. A mere breach of contract remains a civil dispute unless dishonest intention existed from the beginning. This principle remains unchanged under the new criminal framework.

Why Is Dishonest Intention at the Time of Inducement So Important?

Dishonest intention forms the backbone of the offence of cheating. Without mens rea, criminal liability cannot arise. Both IPC and BNS require that the accused intended to deceive the victim at the time of making the representation. Subsequent failure or inability to perform does not automatically lead to criminal prosecution.

The BNS reinforces this requirement. It does not dilute the mental element of the offence. This protects individuals from criminal liability arising out of commercial disputes or failed transactions where criminal intent is absent. Courts will continue to rely on surrounding circumstances to infer intention, just as they did under the IPC regime.

How Does the BNS Reorganize Cheating Provisions Compared to the IPC?

The most visible change lies in structural reorganization. Under the IPC, Section 415 defined cheating, while Section 420 dealt with cheating and dishonestly inducing delivery of property. The BNS restructures these provisions for clarity. Basic cheating now appears under Section 316 of the BNS. Section 321 addresses aggravated forms involving delivery of property and wrongful loss.

This reorganization improves readability without changing substance. The ingredients of offences remain consistent with their IPC counterparts. Judicial precedents interpreting Sections 415 and 420 of the IPC will continue to guide courts when applying Sections 316 and 321 of the BNS.

Does Section 321 BNS Expand or Narrow the Scope of Cheating?

Section 321 of the BNS neither expands nor restricts the scope of cheating. The legislature consciously avoided widening criminal liability. The language may appear modern and streamlined, but the meaning stays the same. The offence still requires deception, inducement, and harm.

The BNS emphasizes wrongful gain and wrongful loss, aligning the provision with contemporary drafting standards. However, this does not alter the threshold for prosecution. Acts that did not amount to cheating under the IPC will not suddenly become criminal under the BNS.

How Is Harm or Damage Interpreted Under the New Law?

Harm remains an essential ingredient of cheating. Both the IPC and the BNS recognize harm that affects property, reputation, body, or mental well-being. The BNS simplifies the phrasing but preserves the legal effect. Actual damage need not always occur. The likelihood of harm is sufficient to attract liability.

This ensures that attempted deception with real consequences remains punishable. At the same time, it prevents over-criminalization by requiring a clear nexus between deception and harm.

Will Old Case Law Still Apply Under Section 321 of the BNS?

Judicial continuity remains one of the strongest features of the new criminal codes. Courts will continue to rely on decades of jurisprudence developed under the IPC. Since the ingredients of cheating remain unchanged, precedents interpreting Sections 415 and 420 IPC retain full relevance.

What Is the Practical Impact of Section 321 BNS on Criminal Prosecution?

In practical terms, Section 321 does not introduce uncertainty. Investigating agencies must still prove dishonest inducement. Prosecutors must still demonstrate intention at inception. Accused persons retain the same defenses that were available under the IPC.

The BNS improves legislative clarity without altering substantive rights. This ensures smoother implementation and reduces the risk of misuse. The offence of cheating remains focused on genuine fraud and deception, not commercial failures or contractual disputes.

Conclusion

The shift from IPC to BNS represents legislative modernization, not legal disruption. Section 321 symbolizes this approach. It preserves the moral and legal foundations of cheating while presenting them in updated language. The continuity ensures stability in criminal justice administration.

For litigants, lawyers, and courts, the message is clear. Cheating under BNS means what cheating always meant under IPC. Deception with dishonest intent remains punishable. Honest failure does not.