Introduction

Section 32 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 creates a vital exception to the rule against hearsay. The general rule excludes statements made outside court. However, this provision recognises that justice cannot depend only on living witnesses. When a person dies or becomes unavailable, their statements may still carry probative value.

Section 32 allows courts to rely on such statements in clearly defined situations. The most important among them is the dying declaration. The law assumes that a person facing death is unlikely to lie. This moral certainty forms the foundation of the provision. At the same time, the law limits admissibility to prevent misuse.

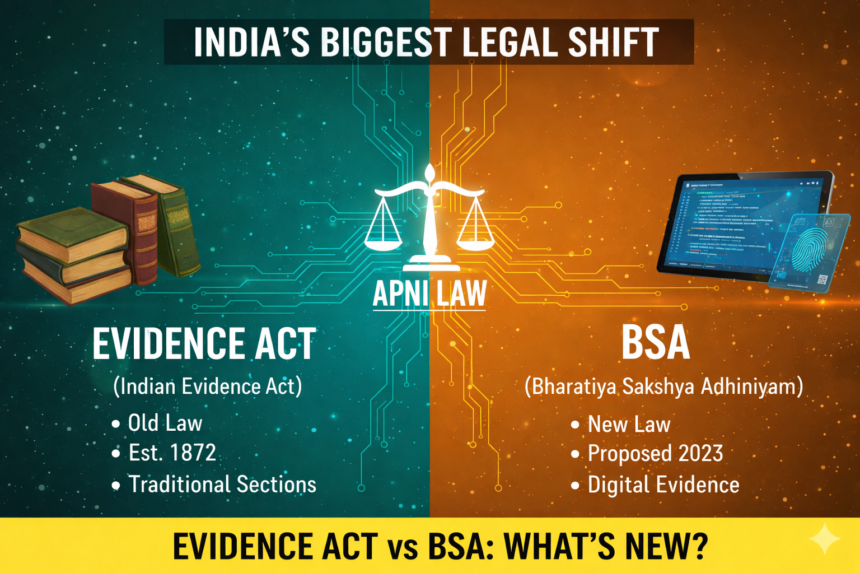

How Does Section 26 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam Replace Section 32?

Section 26 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam, 2023 replaces Section 32 of the Indian Evidence Act with effect from 1 July 2024. The new provision substantially reproduces the old law. The legislature deliberately retained the same structure, language, and legal principles.

This continuity ensures that decades of judicial interpretation remain valid. Courts can continue applying established precedents without disruption. The Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam modernises evidence law while preserving its foundational doctrines.

What Is a Dying Declaration Under Evidence Law?

A dying declaration refers to a statement made by a person about the cause of their death or the circumstances leading to it. Section 32(1) of the Indian Evidence Act and Section 26(1) of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam govern this concept.

The law makes such statements relevant only when the cause of death is directly in issue. The declarant must be dead. The statement must relate to how the death occurred. Importantly, the law does not require the person to expect death at the time of making the statement. This principle distinguishes Indian law from English law.

Why Is a Dying Declaration an Exception to the Hearsay Rule?

The hearsay rule excludes second-hand evidence because it cannot be tested by cross-examination. A dying declaration breaks this rule due to necessity and presumed reliability. The witness is dead. The court has no alternative source of direct evidence.

Courts rely on the belief that a dying person will speak the truth. This belief has moral and legal roots. However, the exception does not operate blindly. Judges carefully examine the surrounding circumstances before accepting such evidence.

Can a Dying Declaration Alone Lead to Conviction?

A dying declaration can form the sole basis of conviction if the court finds it voluntary, truthful, and reliable. Indian courts have consistently affirmed this position. Corroboration is not mandatory as a matter of law.

However, courts exercise great caution. They examine the mental fitness of the declarant. They assess whether the statement was free from tutoring or coercion. Any doubt regarding authenticity weakens evidentiary value. The test is judicial satisfaction, not formal compliance.

Does the Law Require a Magistrate to Record a Dying Declaration?

The law does not mandate that only a magistrate must record a dying declaration. Any person can record it, including a doctor or police officer. Even oral declarations are admissible.

However, declarations recorded by magistrates carry greater credibility. Courts prefer them because they reduce the risk of manipulation. Medical certification of mental fitness strengthens reliability. These factors affect weight, not admissibility.

What Other Statements Are Covered Under Section 32 and Section 26?

Apart from dying declarations, both provisions cover six other categories of statements. These include statements relating to family relationships, such as legitimacy or adoption. They also include statements concerning customs, usages, and rights attached to customs.

Statements regarding the existence of marriage also fall within the scope. Statements made in the ordinary course of business are included. Statements against interest and statements relating to public rights are also admissible. These categories prevent injustice when direct testimony becomes impossible.

Why Are These Additional Exceptions Necessary?

Life produces disputes that outlive people. Property rights, family status, and customary entitlements often depend on historical facts. Witnesses may die before litigation begins. Without these exceptions, many genuine claims would fail.

The law therefore allows reliable past statements to fill evidentiary gaps. It limits admissibility to situations where the statement naturally carries credibility. Courts still examine relevance and consistency before relying on such evidence.

Does Section 26 BSA Introduce Any Substantive Changes?

Section 26 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam does not introduce substantive changes. The wording of clauses (1) to (7) remains materially identical to Section 32 of the Indian Evidence Act. The treatment of dying declarations remains unchanged.

The absence of change reflects legislative satisfaction with existing law. Judicial precedents such as Laxman v. State of Maharashtra continue to guide interpretation. The principles of voluntariness, mental fitness, and reliability remain central.

How Do Courts Assess the Reliability of Statements Under These Provisions?

Courts assess reliability by examining the context of the statement. They consider who recorded it and how it was recorded. They evaluate consistency with medical and circumstantial evidence. They also consider whether the declarant had an opportunity to observe the facts stated.

If the statement inspires confidence, courts rely on it. If doubts arise, courts reject it or seek corroboration. The judge acts as a gatekeeper of evidentiary trust.

Conclusion

Despite technological advancements, human mortality remains unchanged. Witnesses still die. Memories still fade. Section 32 of the Indian Evidence Act and Section 26 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam ensure that truth does not perish with the witness.

By retaining these provisions, the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam balances tradition with modernity. It protects fairness while addressing practical necessity. These exceptions continue to serve as pillars of substantive justice in Indian evidence law.