Introduction

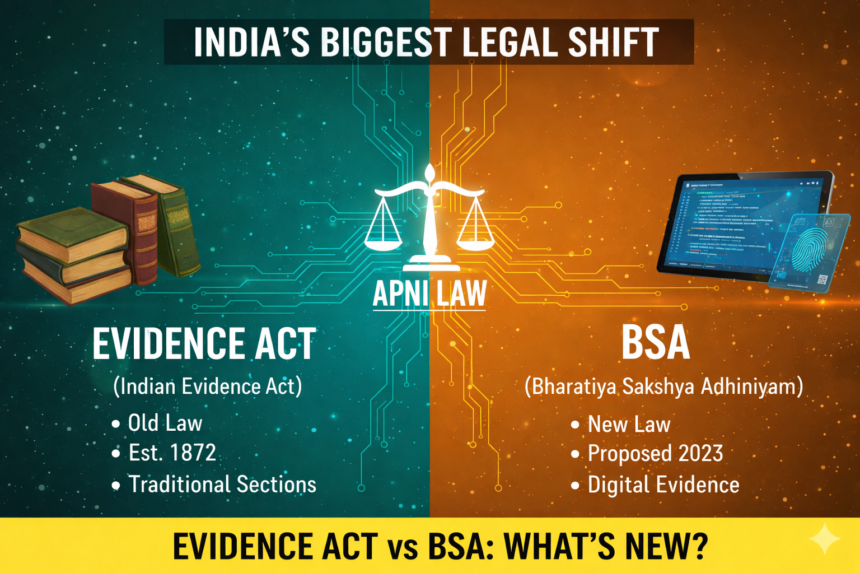

Indian criminal jurisprudence has consistently treated confessions made to police officers with suspicion. The law recognizes the unequal power relationship between the police and the accused. It assumes a real risk of coercion, intimidation, or inducement. To protect the rights of the accused and to ensure fair trials, Indian evidence law prohibits the use of police confessions as substantive evidence. This principle existed under the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 and continues under the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam, 2023, which came into force on 1 July 2024.

What does Section 25 of the Indian Evidence Act state?

Section 25 of the Indian Evidence Act imposes an absolute bar on the admissibility of confessions made to police officers. The section clearly states that no confession made to a police officer shall be proved as against a person accused of any offence. The provision does not distinguish between custody and non-custody situations. Even if the accused speaks voluntarily, the confession remains inadmissible.

Courts have repeatedly clarified that this bar applies only to the confessional portion of the statement. If the accused makes a mixed statement containing both confessional and non-confessional facts, only the confession is excluded. Independent facts, if otherwise relevant, may still be admissible. This strict rule reflects the legislative intent to eliminate any incentive for forced confessions during police investigation.

Does Section 25 allow any exceptions for police confessions?

Section 25 itself contains no exceptions. However, courts have read it alongside Section 27 of the Evidence Act. Section 27 allows the admissibility of information received from an accused in police custody if that information distinctly leads to the discovery of a fact. Only the portion of the statement directly connected to the discovery becomes admissible. The confession itself remains excluded.

This limited exception balances investigative needs with individual liberty. It allows courts to rely on objective discoveries rather than subjective admissions of guilt.

How does Section 23 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam deal with confessions?

Section 23 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam replaces Sections 25, 26, and 27 of the Evidence Act through a consolidated structure. Subsection (1) retains the core rule. It states that a confession made to a police officer shall not be proved against the accused. This maintains full continuity with Section 25 of the old Act.

The legislature deliberately preserved this prohibition. It reflects judicial experience and constitutional values under Articles 20(3) and 21 of the Constitution. The new law confirms that procedural reform does not dilute substantive protections.

What is the significance of Section 23(2) of the BSA?

Section 23(2) introduces express language on custodial confessions. It provides that no confession made while the accused is in police custody shall be proved unless it is made in the immediate presence of a Magistrate. This provision codifies what was earlier contained in Section 26 of the Evidence Act.

By integrating custody-based exclusions directly into Section 23, the BSA improves legislative clarity. It removes the need to interpret multiple provisions together. The presence of a Magistrate acts as a safeguard against coercion and ensures voluntariness.

Does the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam retain the discovery exception?

The BSA retains the discovery exception through a proviso to Section 23(2). This proviso allows the admissibility of so much of the information given by the accused as distinctly relates to the discovery of a fact. The language closely mirrors Section 27 of the Evidence Act.

The courts will continue to apply established judicial tests. The prosecution must show that the accused was in custody, the information led to discovery, and only the discovery-linked portion is admitted. The confession of guilt remains excluded.

How do the two laws differ in structure but not substance?

The major difference between Section 25 of the Evidence Act and Section 23 of the BSA lies in structure rather than substance. The Evidence Act spread the law on confessions across three sections. The BSA consolidates them into one section with subsections and a proviso. This drafting change enhances readability and interpretive certainty.

Substantively, both laws pursue the same objective. They exclude police confessions, discourage coercive practices, and uphold procedural fairness. Courts are likely to rely on existing precedents while interpreting Section 23 of the BSA.

Do earlier judicial interpretations still apply under the BSA?

Judicial interpretations developed under the Evidence Act continue to hold relevance. Courts have consistently distinguished between confessional statements and statements of fact. They have also clarified the scope of discovery-based admissibility. Since the BSA does not alter these core principles, earlier case law will guide interpretation.

Unless the Supreme Court explicitly departs from settled doctrine, principles governing voluntariness, custody, and discovery will remain unchanged.

Conclusion

The Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam does not weaken protections against police-induced confessions. Instead, it reinforces them through clearer drafting. Section 23 preserves the absolute bar on police confessions, strengthens safeguards for custodial statements, and retains the narrow discovery exception.

In effect, the BSA modernizes the language of evidence law without compromising constitutional values. The legal position on confessions to police officers remains firmly rooted in the principles of fairness, voluntariness, and due process.