Introduction

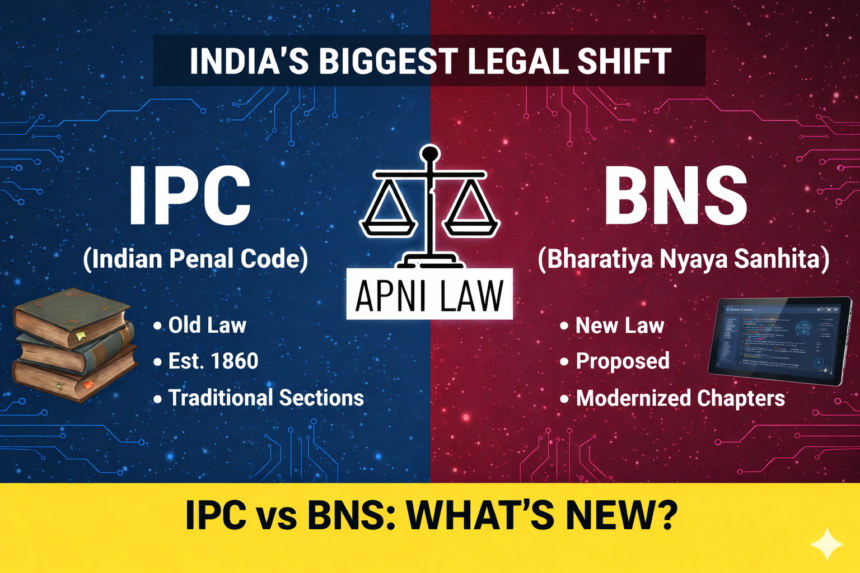

Section 113 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 replaces and corresponds directly to Section 149 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. Both provisions deal with the principle of vicarious liability arising from unlawful assembly and the concept of a common object. The core idea remains unchanged. If a crime is committed by any member of an unlawful assembly in furtherance of the common object, every member becomes legally responsible. The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita does not alter the substance of this rule. It reorganises and consolidates the law to improve clarity and application.

The shift from IPC to BNS reflects legislative modernization rather than doctrinal reform. Courts continue to apply the same judicial principles developed under Section 149 IPC while interpreting Section 113 BNS.

What Is the Legal Purpose of Section 149 IPC and Section 113 BNS?

Section 149 IPC establishes collective criminal liability. It holds that every member of an unlawful assembly is guilty of an offence committed in prosecution of the common object of that assembly. Liability also arises when members knew that such an offence was likely to be committed. Section 113 BNS adopts identical language and intent. It preserves the doctrine that individual participation in the criminal act is not mandatory for guilt.

The law aims to prevent group violence and organised crime. It discourages individuals from hiding behind collective action. By criminalising shared responsibility, both provisions strengthen public order and deterrence.

How Do Both Laws Define an Unlawful Assembly?

Under the IPC, an unlawful assembly is defined in Section 141. It requires a minimum of five persons with a common object specified by law, such as resisting lawful authority or using criminal force. The BNS retains this threshold. However, it relocates the definition to Section 187 and consolidates related provisions that earlier existed between Sections 141 and 154 IPC.

The essential elements remain unchanged. The prosecution must still establish the numerical strength, the existence of a common object, and the unlawful nature of that object. Structural consolidation under BNS simplifies interpretation but does not expand criminal liability.

What Does “Common Object” Mean in Both Provisions?

Common object lies at the heart of both Section 149 IPC and Section 113 BNS. It refers to the shared purpose that unites the members of the unlawful assembly. Unlike common intention under Section 34 IPC, common object does not require prior planning. It may form suddenly and evolve during the incident.

Courts infer common object from conduct, circumstances, weapons carried, slogans raised, and the nature of injuries inflicted. Section 113 BNS continues to rely on these evidentiary principles. The prosecution must prove that the offence committed had a direct nexus with the common object or was a foreseeable outcome.

Is Mere Presence Enough to Attract Liability?

Mere physical presence at the scene of crime does not automatically attract liability under either law. Courts consistently hold that the accused must be shown to be a member of the unlawful assembly sharing the common object. However, active participation in the crime is not mandatory.

Section 113 BNS, like Section 149 IPC, allows courts to draw inferences from behaviour. Presence combined with conduct, support, or failure to dissociate may establish membership. Passive spectators are excluded, but silent supporters are not.

How Does Punishment Work Under Section 113 BNS and Section 149 IPC?

Neither provision prescribes a separate punishment. Instead, every member of the unlawful assembly receives the same punishment as the principal offender. This rule applies irrespective of the degree of individual involvement.

The BNS retains this framework without modification. The severity of punishment depends entirely on the underlying offence, such as murder, grievous hurt, or rioting. This ensures parity and reinforces the principle of collective responsibility.

How Have Courts Interpreted These Provisions?

Judicial interpretation developed under Section 149 IPC continues to guide the application of Section 113 BNS. The Supreme Court has repeatedly stressed that common object must be established beyond reasonable doubt. Courts rely on circumstantial evidence rather than direct proof.

Judgments emphasise caution to avoid false implication due to group rivalry. At the same time, courts uphold convictions where evidence demonstrates coordinated action or shared intent. The BNS does not introduce any new evidentiary standards. It merely carries forward settled jurisprudence.

Does the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita Change Anything Substantively?

The BNS does not alter the legal doctrine of unlawful assembly or vicarious liability. Its contribution lies in structural clarity. It groups related offences such as rioting and armed assembly under fewer sections. This reduces overlap and improves accessibility.

Conclusion

Section 113 BNS represents continuity with refinement. It preserves the core philosophy of collective liability while streamlining statutory structure. The law against unlawful assembly remains robust and unchanged in substance. The emphasis stays on preventing group-based criminality through shared responsibility.

In essence, Section 113 BNS stands as a modern restatement of Section 149 IPC, ensuring that the principle of common object continues to play a central role in India’s criminal justice system.