Introduction

The Indian Constituent Assembly holds a proud place in history as the assembly that framed the Constitution, endowing India with its democratic structure. It was the platform where the leaders deliberated the basics of rights, federalism, and protection for minorities, and formulated the basis of the Republic. However, along with applause, the Assembly has also been subjected to heavy criticism. Scholars, politicians, and observers have queried whether the Assembly was representative of India’s vast and multifarious population. Questions on its election method, social inclusivity, and political dominance have long informed arguments on its democratic nature. In order to determine this, it is important to go back and see how the Assembly was established and examine if it best represented the will of the people of India.

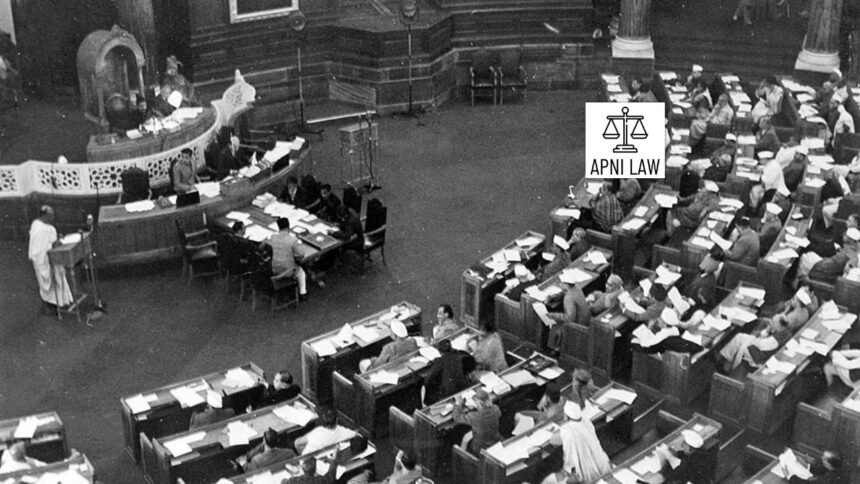

How the Constituent Assembly Was Formed

The Constituent Assembly was formed in 1946 by the Cabinet Mission Plan, whereby a plan for framing an independent India’s constitution was framed. Members of the Constituent Assembly were indirectly elected to the provincial legislatures, and princely states nominated them. Hence, Indians did not directly elect the Assembly. When India’s population stood almost at 400 million, less than one-sixth of adult citizens had the franchise under colonial laws subject to property, tax, and education qualifications.

The Assembly originally consisted of 389 members, which represented provinces, princely states, and minorities. Later, the number decreased to 299 due to the withdrawal of several Muslim League representatives during the Partition of 1947. Prominent leaders such as Dr. Rajendra Prasad, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, and Maulana Azad were part of the Assembly. However, India’s vast majority of poor, illiterate, and marginalized people were not represented directly.

Criticism: Lack of Direct Elections

One of the most frequent criticisms is that the Constituent Assembly was not universal adult suffrage-based. As the people themselves did not choose its members, it was argued by critics that the Assembly never received the full democratic legitimacy. Although it framed a Constitution which eventually gave the vote to all adults, the process of formulation was dominated by political elites and provincial legislature members instead of the masses.

Congress Party Domination

Another area of criticism is the sheer dominance of the Indian National Congress. As Congress had won a sweep in the provincial elections in 1937 and was the best-organized political force, it held a majority of seats in the Assembly. This rendered it challenging for smaller parties or individual voices to have a lasting influence. Critics note that although the Assembly deliberated at length and incorporated amendments proposed by numerous members, the general vision of the Constitution broadly agreed with the Congress ideology of parliamentary democracy and a centralized government.

Minority Representation and Inclusiveness

The representation of minorities is also a cause for concern regarding the representative nature of the Assembly. The majority of Muslim League members left the Assembly after Partition, decreasing Muslim representation considerably. Even though leaders such as Maulana Azad continued to work, their lack of opposition diluted pluralism in the Assembly.

The princely states, which comprised almost one-third of India’s land area, were represented by nomination and not election. Most of the representatives were not elected by the people but nominated by the rulers. Likewise, Scheduled Castes and tribes did have some representation, but critics assert that marginalized voices were still not sufficiently robust to counterbalance elite dominance.

Elitist Character of the Assembly

The social composition of the Constituent Assembly also raised criticisms. Most members were lawyers, professionals, landlords, or members of privileged sections. There were hardly any women, only a handful of 15 members out of close to 300, and minimal representation of peasants, workers, or other classes of society who comprised the bulk of India’s population. This elitist nature of the Assembly was such that some critics view it as not a reflection of Indian society but rather a conclave of leaders.

Defending the Representativeness of the Assembly

Though these are correct, yet there are people who defend the Assembly on the ground that, given the 1940s situation, it was as representative as could be. India was newly independent from colonial rule, and elections based on universal adult franchise were practically impossible to hold. The Assembly had representation from all parts of the country, all religions, and all communities such as Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Anglo-Indians.

In addition, the debates within the Assembly exhibited profound concern for inclusivity. Fundamental Rights, minority protection, Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes reservation, and federal protection all demonstrate that the Assembly attempted to be inclusive of India’s diversity. Ambedkar and other leaders demanded provisions for social justice, while Nehru and Patel labored to integrate minorities and princely states into the constitutional scheme.

Balancing the Criticism

The Constituent Assembly might not have been ideally representative, but it managed to craft one of the globe’s most elaborate and democratic constitutions. Though the lack of universal suffrage and dominance by elites are valid objections, the Assembly made up for it by debating freely and leaving room for several views. The process may have been constrained by the political conditions of the day, but the product, the Constitution, provided universal adult franchise, equality before the law, and safeguards for rights to all Indians.

Conclusion

The Constituent Assembly of India was a reflection of its times and a landmark in the democratic evolution of India. It was rightly criticized for not being elected directly, for being controlled by Congress, and for having an elitist nature with limited representation of minorities and weaker sections. Nevertheless, it would be unjust to label the Assembly as non-representative. For all its deficiencies, it came up with a Constitution that has withstood the test of time and continues to steer India’s democracy.

The issue of whether the Assembly was really representative may never be able to be answered simply. What cannot be dismissed, however, is that it provided a democratic system that empowered all Indian citizens, making sure that future generations would have a direct say in shaping the country through universal suffrage.

For any specific query call at +91 – 8569843472