Introduction

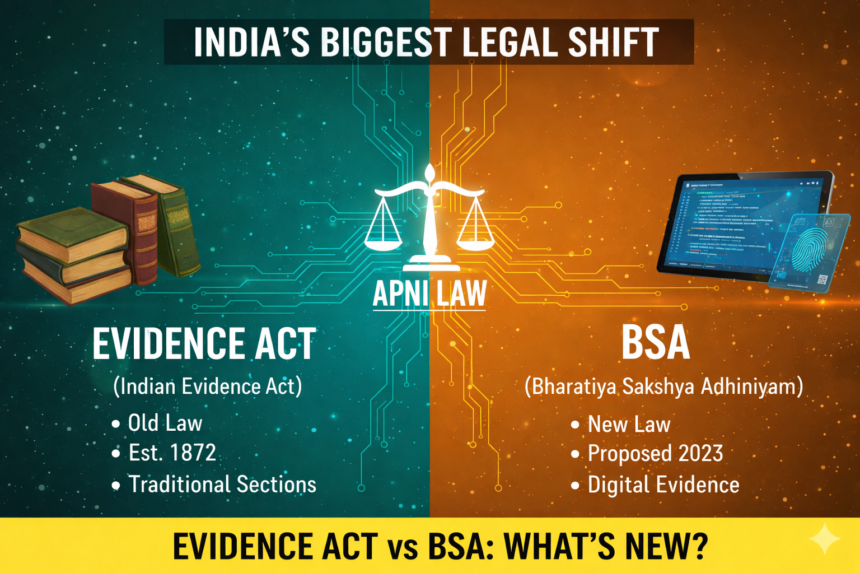

Section 27 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 played a crucial role in criminal trials by carving out a narrow but powerful exception to the general rule that confessions made to police officers are inadmissible. It allowed courts to rely on that limited portion of an accused person’s statement which directly led to the discovery of a fact. With the enactment of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam, 2023, the legislature did not discard this principle. Instead, it restructured it. Section 25 of the BSA consolidates the earlier Sections 25, 26, and 27 of the Evidence Act into a single comprehensive provision dealing with police confessions, while retaining the discovery exception in almost identical language. The change is structural, not substantive, ensuring continuity in legal interpretation.

Why Was Section 27 of the Indian Evidence Act So Important?

Section 27 of the Evidence Act acted as a proviso to the strict bar imposed by Sections 25 and 26. While those sections excluded confessions made to police officers or while in police custody, Section 27 recognised a practical reality. If information given by an accused led the police to discover a new fact, such as a hidden weapon or stolen property, then justice demanded that the law take note of it. The provision therefore allowed courts to admit only that specific part of the statement which distinctly related to the discovered fact. This careful balance protected accused persons from coercion while still enabling effective investigation.

How Does Section 25 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam Reshape the Law?

Section 25 of the BSA represents legislative consolidation rather than reform. It brings together the rules on confessions to police officers and confessions made in custody under one umbrella. The main provision reiterates that confessions made to police officers, or while in police custody without the presence of a Magistrate, are not admissible. Crucially, the proviso reproduces the discovery exception almost word for word from Section 27 of the Evidence Act. This drafting choice signals a clear intention to preserve decades of judicial interpretation and settled principles relating to discovery of facts.

Is the Language of the Discovery Exception Really Unchanged?

Yes, the language of the discovery proviso under the BSA remains virtually verbatim. It continues to state that when any fact is discovered in consequence of information received from an accused person in police custody, only so much of that information as distinctly relates to the fact discovered may be proved. This continuity ensures that courts can continue to apply landmark judgments without reinterpretation. The legislature has consciously avoided altering expressions like “fact discovered” or “relates distinctly,” both of which carry deep judicial meaning.

What Conditions Must Be Satisfied for Admissibility Under Both Laws?

Both Section 27 of the Evidence Act and Section 25 of the BSA impose strict conditions for admissibility. The accused must be in police custody at the time of giving the information. The information must lead to the discovery of a fact that was previously unknown to the police. The prosecution must prove the discovery through reliable testimony. Most importantly, only that portion of the statement which directly connects to the discovered fact is admissible. Any confessional or self-incriminating narrative beyond this limited scope remains excluded.

What Exactly Does “Fact Discovered” Mean in Practice?

Courts have consistently interpreted “fact discovered” to include more than the mere physical object recovered. It also encompasses the place from which the object is recovered and the accused’s knowledge of that place. For example, when an accused states that a knife used in the offence is buried under a specific tree and the police recover it from there, the admissible portion is limited to the information that leads to that recovery. Statements admitting guilt or describing how the crime was committed do not become admissible merely because a recovery followed.

Does the BSA Change the Role of Magistrates in Confessions?

The BSA reinforces the rule that confessions made in police custody require the immediate presence of a Magistrate to be admissible. This safeguard remains consistent with constitutional protections against self-incrimination. However, the discovery proviso continues to operate independently of Magistrate presence. Even without a Magistrate, the law permits proof of the discovery-related portion of the accused’s statement. This reflects the same balance that existed under the Evidence Act between individual rights and investigative necessity.

How Have Courts Viewed Discovery Statements Historically?

Judicial precedents, including landmark decisions such as Mohd. Inayatullah v. State of Maharashtra, have laid down clear guidelines for applying the discovery rule. Courts stress that the information must be voluntary, precise, and directly connected to the discovery. They also caution against mechanical reliance on recovery memos, emphasising that the discovery must genuinely reveal a new fact. Since the BSA retains the same wording, these principles continue to guide courts without interruption.

What Are the Practical Implications for Investigations and Trials?

From a practical standpoint, the enactment of the BSA does not alter the evidentiary value of recoveries made pursuant to disclosure statements. Investigating agencies can continue to rely on discovery-based evidence, provided they strictly comply with legal requirements. Defence counsel can equally continue to challenge recoveries on grounds of voluntariness, prior knowledge, or lack of exclusive discovery. The renumbering and consolidation simply make the statute more streamlined and accessible without disturbing the substantive law.

Conclusion

In substance, the answer is no. Section 25 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam preserves the essence of Section 27 of the Indian Evidence Act. The discovery exception survives intact, along with all its judicial safeguards and limitations. The law on discovery of facts and recoveries remains exactly where it stood, ensuring legal certainty and continuity. For students, lawyers, and judges, the shift is one of form, not function.