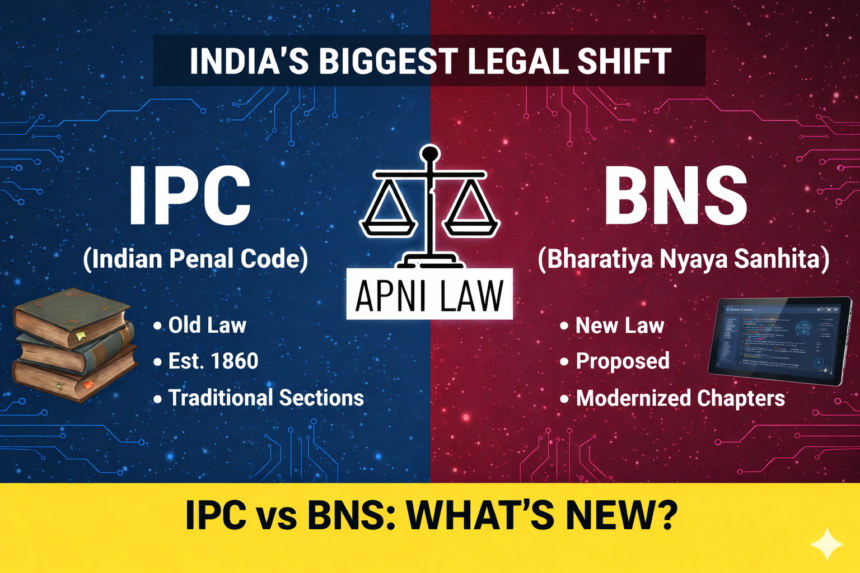

Introduction

Section 152 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita marks a clear departure from the colonial-era sedition offence under Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code. Instead of criminalising “disaffection against the Government,” the new provision targets acts that endanger the sovereignty, unity, and integrity of India. This shift reframes the offence from protecting the authority of a ruling government to safeguarding the constitutional existence of the Indian State itself. While lawmakers present Section 152 as a modern and democratic replacement, debates continue on whether it genuinely resolves long-standing concerns of overbreadth and misuse that surrounded sedition law.

What Interest Did Section 124A IPC Protect?

Section 124A IPC focused on speech or expression that brought hatred, contempt, or disaffection toward the Government established by law in India. The protected interest was the stability and authority of the Government, a concept inherited from colonial rule where criticism of the administration was equated with threats to the State. Although courts later clarified that the “Government” did not mean individual ministers, the core concern remained the preservation of governmental authority rather than the protection of constitutional sovereignty or territorial integrity.

What Interest Does Section 152 BNS Protect?

Section 152 BNS shifts the protected interest to the sovereignty, unity, and integrity of India. It criminalises acts that incite secession, armed rebellion, or subversive activities, or that encourage separatist feelings. The emphasis now lies on preventing conduct that threatens India as a nation-state, not on suppressing criticism of those in power. This change aligns the offence more closely with constitutional values and national security concerns, at least in theory, by tying criminality to threats against the country rather than against the government of the day.

How Do the Mental Elements Compare Under Both Laws?

Section 124A IPC did not expressly require intent to cause violence or public disorder in its text. It penalised speech with a “tendency” to excite disaffection, which allowed wide discretion to law enforcement. This vagueness enabled frequent use of sedition charges against journalists, activists, and political opponents. In contrast, Section 152 BNS explicitly uses the words “purposely or knowingly,” indicating a higher threshold of culpability. By linking liability to intentional or knowing acts that incite secession or rebellion, the new provision seeks to narrow the offence to deliberate threats rather than inadvertent or emotional expressions.

Does Section 152 BNS Require Concrete Harm?

Judicial interpretation played a crucial role in limiting Section 124A IPC. In Kedarnath Singh, the Supreme Court upheld sedition but confined it to acts involving incitement to violence or public disorder. Without this reading down, the provision would have remained dangerously broad. Section 152 BNS attempts to embed this limitation within the statutory language itself by focusing on secessionist and armed activities. However, the provision still uses broad terms such as “encourages separatist feelings,” which may not always require immediate or concrete harm. Until courts clarify these expressions, uncertainty persists about how narrowly the offence will be applied.

What Safeguards Exist Under the New Provision?

Section 124A IPC benefited from decades of constitutional interpretation that shielded legitimate dissent from prosecution. Repeated Supreme Court judgments reinforced that strong criticism of government policy does not amount to sedition unless it incites violence. Section 152 BNS lacks this accumulated judicial guidance. While early commentary stresses that it must not stifle dissent, the absence of explicit statutory illustrations or safeguards means its limits remain undefined. The real protection will depend on how higher courts interpret “purpose,” “knowledge,” and “endangerment” in future cases.

Why Was Section 124A IPC Replaced at All?

Sedition law under Section 124A symbolised colonial repression. Introduced in 1870, it aimed to silence opposition to the British Raj. Even after independence, its continued use conflicted with modern free speech standards under Article 19(1)(a). The Supreme Court’s 2022 decision in SG Vombatkere, which effectively paused the use of sedition, underscored this constitutional tension and forced legislative reconsideration. Section 152 BNS emerged from this backdrop as an attempt to retain a national security offence while discarding colonial terminology and intent.

Does Section 152 BNS Still Threaten Free Speech?

Supporters argue that Section 152 BNS targets only serious threats like secession and armed rebellion, not peaceful protests or criticism of government policies. Critics counter that broad phrases and the inclusion of electronic communication and financial means could still chill speech. The fear is not only about convictions but about the process itself, where arrest and prosecution become tools of intimidation. Without careful judicial oversight, the provision risks replicating the same chilling effects that plagued sedition law.

How Do Punishments Compare?

Section 124A IPC allowed punishment up to life imprisonment, making it one of the harshest speech-related offences in Indian law. Section 152 BNS reduces the maximum punishment to seven years with fine, signalling a recalibration toward proportionality. At the same time, it expands the modes of commission to include digital communication and financial support, reflecting modern realities of subversive activity. This combination narrows the offence in theory but broadens it technologically.

Conclusion

The core shift from Section 124A IPC to Section 152 BNS lies in moving from punishing disaffection against government to penalising intentional acts that threaten India’s sovereignty and integrity. Whether this doctrinal change results in meaningful protection for free speech will depend on cautious interpretation and principled enforcement. The law’s promise lies in its focus on real threats, but its legitimacy will ultimately rest on how responsibly it is applied in practice.