Introduction

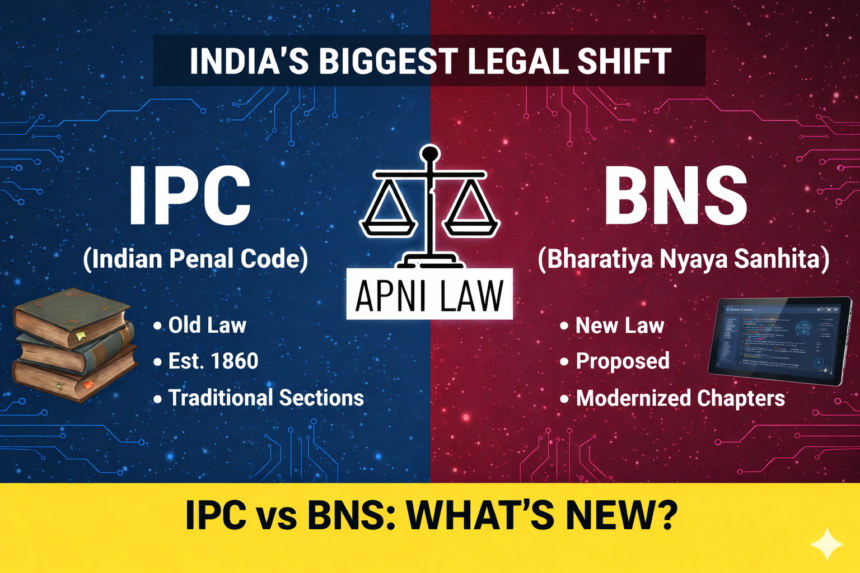

Criminal law does not only punish those who directly commit an offence. It also extends liability to individuals who encourage, provoke, or assist others in committing crimes. This idea forms the foundation of the law of abetment. Under the Indian Penal Code, abetment was defined under Section 107, while punishment-related provisions followed separately. With the introduction of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, the concept of abetment has been re-enacted under Section 109.

Although the numbering and drafting have changed, the essence of abetment remains largely intact. The shift from IPC to BNS reflects legislative continuity combined with a conscious effort to modernise language and structure. Understanding this comparison is essential for law students, practitioners, and anyone seeking clarity on India’s evolving criminal justice framework.

What Is Abetment Under Section 107 IPC?

Section 107 of the IPC defined abetment through three distinct modes. A person abets an offence when they instigate another person to commit it, engage in a conspiracy for its commission, or intentionally aid the offence by an act or illegal omission. The law focused on the role played by the abettor rather than on the final execution of the crime.

Judicial interpretation under the IPC clarified that instigation involves active encouragement or provocation. It does not include casual remarks or expressions made without intent. Similarly, intentional aid requires conscious assistance. Accidental help or unknowing involvement does not satisfy this requirement. Courts consistently held that abetment depends heavily on intention and knowledge.

Section 107 IPC was only a definitional provision. Punishment for abetment depended on other sections, primarily Section 109 IPC, when the offence was committed as a result of abetment.

How Does Section 109 BNS Explain Abetment?

Section 109 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita carries forward the same threefold understanding of abetment. Instigation, conspiracy, and intentional aid continue to form the backbone of the offence. The provision does not dilute the requirement of intention, nor does it expand liability beyond established legal limits.

The most noticeable change lies in drafting style. The BNS adopts simpler and more contemporary language. It avoids archaic expressions that were common in the IPC. This shift improves readability without altering legal meaning. As a result, the provision becomes more accessible to investigators, lawyers, and even ordinary citizens.

Importantly, courts can still rely on decades of IPC-based judgments because the substance of the law remains unchanged. This ensures stability in criminal jurisprudence during the transition.

Is the Mental Element Still Central to Abetment?

Both Section 107 IPC and Section 109 BNS place strong emphasis on mens rea. Abetment is not a strict liability offence. The prosecution must establish that the accused had a conscious intention to facilitate the commission of the offence.

Mere presence at the scene of crime or passive knowledge does not amount to abetment. Even moral support, unless coupled with intention and encouragement, falls short of legal abetment. The BNS retains this approach, thereby protecting individuals from unjust prosecution based on suspicion or association alone.

This continuity reinforces the principle that criminal liability must rest on both action and intention.

How Is Punishment for Abetment Handled Under BNS?

Under the IPC framework, punishment for abetment depended on whether the offence was actually committed. When an offence occurred as a result of abetment, the abettor generally faced the same punishment as the principal offender unless the law provided otherwise. This principle continues under the BNS.

Section 109 BNS ensures proportional punishment by linking the liability of the abettor to the gravity of the offence. Serious crimes attract severe punishment, while lesser offences receive proportionate treatment. This approach maintains fairness while recognising the significant role played by abettors in enabling crime.

Does the BNS Expand or Restrict the Scope of Abetment?

The BNS does not significantly expand or restrict the scope of abetment. Instead, it consolidates existing principles in a clearer framework. Liability for abetment can still arise even if the offence is not successfully completed, provided the law recognises such liability.

At the same time, safeguards remain strong. Courts still require clear evidence of instigation or intentional aid. The standard of proof remains high, ensuring that abetment provisions do not become tools for over-criminalisation.

Why Does Abetment Remain Relevant in Modern Criminal Law?

Modern crimes often involve multiple actors operating at different levels. Financial scams, cyber crimes, organised violence, and even offences against the state frequently rely on planners and facilitators rather than lone perpetrators. Abetment provisions ensure that such individuals do not escape accountability simply because they did not carry out the final act.

By retaining the core principles of Section 107 IPC within Section 109 BNS, the legislature acknowledges the continuing importance of indirect criminal liability in maintaining law and order.

Conclusion

Section 109 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita represents continuity with refinement. It preserves the foundational principles of abetment laid down under Section 107 of the IPC while presenting them in clearer and more modern language. The mental element, modes of abetment, standards of proof, and proportional punishment remain consistent with established jurisprudence.

For anyone studying or practising criminal law, this comparison highlights that the BNS builds upon familiar legal concepts rather than replacing them entirely. Abetment continues to play a vital role in ensuring that those who encourage, assist, or facilitate crime are held accountable under India’s evolving criminal justice system.