Introduction

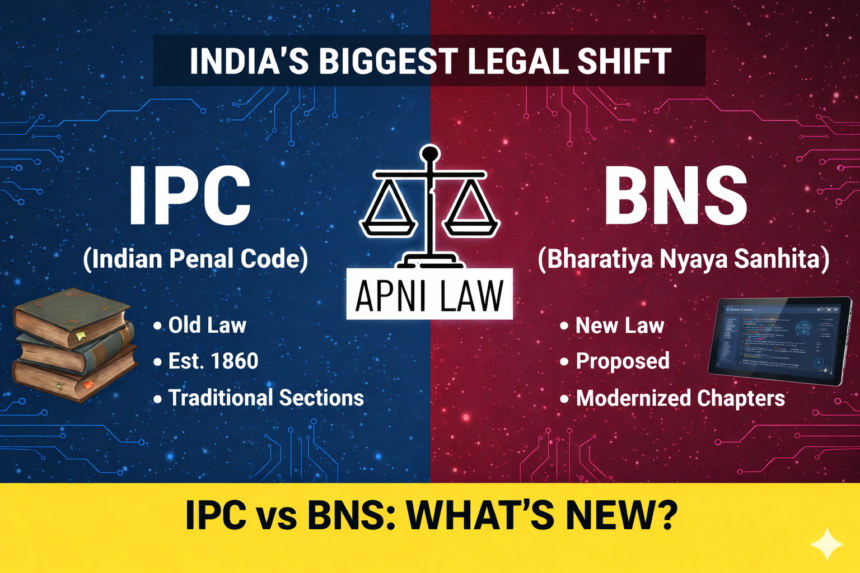

Murder has always occupied the most serious place in Indian criminal law. It represents an extreme violation of the right to life guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution. Under the Indian Penal Code, 1860, Section 302 governed the punishment for murder for more than a century. With the introduction of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, Section 101 replaces this provision while retaining the gravity of the offence. Although the core definition of murder remains rooted in established principles, the new law attempts to modernise language, streamline interpretation, and align punishment with contemporary criminal justice philosophy.

What did Section 302 IPC provide for murder?

Section 302 IPC prescribed punishment for murder as death or imprisonment for life, along with fine. The provision operated in conjunction with Section 300 IPC, which defined when culpable homicide amounts to murder. Courts relied heavily on judicial precedents to distinguish murder from culpable homicide not amounting to murder, especially in cases involving intention, knowledge, and exceptions such as grave and sudden provocation.

Over time, judicial interpretation gave depth to this provision. In Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab (1980), the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the death penalty but limited its application to the “rarest of rare” cases. This judgment significantly shaped sentencing under Section 302 IPC and introduced proportionality into punishment.

How does Section 101 BNS redefine punishment for murder?

Section 101 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita continues to treat murder as one of the gravest offences against society. It prescribes punishment of death or imprisonment for life, along with fine, similar to Section 302 IPC. However, the drafting under BNS uses clearer and more direct language, making the provision easier to understand for both legal professionals and the general public.

While the punishment structure remains largely unchanged, the BNS reflects a more victim-centric and constitutional approach. Courts are expected to apply sentencing principles consistently, keeping in mind reformative justice alongside deterrence. The continued recognition of the “rarest of rare” doctrine ensures that capital punishment remains an exception rather than the norm.

Has the definition of murder changed under BNS?

The substantive understanding of murder under the BNS remains aligned with the long-standing principles developed under IPC jurisprudence. Intention to cause death, intention to cause bodily injury sufficient in the ordinary course of nature to cause death, and knowledge that the act is so imminently dangerous continue to form the foundation of the offence.

What changes is not the essence of murder but the legislative clarity. The BNS avoids archaic phrasing and promotes a uniform reading of offences. This reduces ambiguity and ensures that decades of judicial interpretation under the IPC remain relevant while operating within a modern statutory framework.

What is the impact on sentencing and judicial discretion?

Both Section 302 IPC and Section 101 BNS vest significant discretion in courts when deciding punishment. However, under the BNS regime, sentencing is expected to be more structured and consistent. Courts increasingly focus on aggravating and mitigating circumstances, the conduct of the accused, and the impact on victims’ families.

Judgments such as Machhi Singh v. State of Punjab continue to guide courts in identifying cases where the death penalty may be justified. At the same time, life imprisonment without remission has emerged as a viable alternative, reinforcing the balance between justice and human rights.

Does Section 101 BNS strengthen victim-centric justice?

One noticeable shift under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita is the broader emphasis on victims’ rights. Although Section 101 itself deals with punishment, it operates within a legal ecosystem that places greater importance on victim compensation, speedy trials, and procedural fairness. This reflects a holistic reform approach rather than a narrow focus on punishment alone.

By retaining strict punishment for murder while embedding it in a reform-oriented criminal justice system, the BNS aims to address both societal outrage and constitutional values.

Conclusion

Section 101 BNS largely mirrors Section 302 IPC in terms of punishment and seriousness of the offence of murder. However, the transition from IPC to BNS represents more than a numerical change. It reflects an effort to modernise criminal law, enhance clarity, and harmonise punishment with constitutional principles. Murder remains a heinous crime, but its prosecution and sentencing now operate within a framework that emphasises fairness, consistency, and dignity. The BNS thus carries forward established jurisprudence while preparing Indian criminal law for contemporary challenges.